Feb. 4, 2021

Rectangular Collision Detection in D3 Force Layouts

Collision detection is a problem that comes up a lot in game development, and also in designing physical simulations, where the goal is to detect intersecting objects.

Collision detection in D3.js

In D3, a force layout graph works as a physical simulation.

I'm assuming some familiarity with force layouts in D3 here - check out some of the posts in the sidebar if you're totally unfamiliar with them.

In this post we're going to adapt a built-in force in D3 that handles collision detection with circles for use with rectangles.

- You can find the code here.

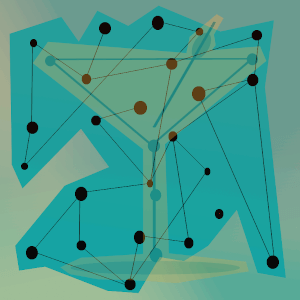

D3 force layout

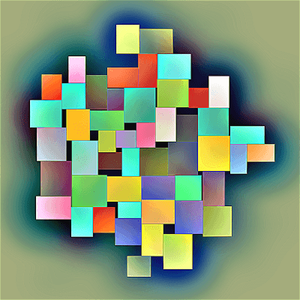

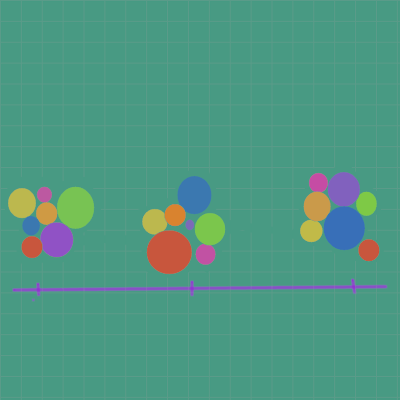

You might have worked with bubble charts, or a basic network graph where the nodes are circles.

Setting up a force layout can be pretty straightforward:

- Start with your data for the graph nodes and sometimes links (we're ignoring links today).

- Initialize a simulation.

- Assign some forces to it.

- Define a tick function to update the position of the circles as the simulation progresses.

Often a combination of forces work together to repel and/or attract nodes from one another to create the desired layout.

One such force works to correct overlapping nodes by detecting when two nodes are colliding and then correcting the overlap.

forceCollide

D3 has a built-in force for collision detection, forceCollide, which works on circles.

But what if you're working with rectangles instead of circles?

- forceCollide uses the radius of the circle to detect a collision and correct it.

In this post we will adapt forceCollide to work on rectangles.

The new force will be called rectCollide and can be used in a simulation like:

var simulation = d3.forceSimulation()

.force('collision', rectCollide().size(function(d){return [d.width,d.height]}))

.nodes(nodes);

But let's not get ahead of ourselves quite yet.

How does collision detection work?

Two basic shapes in 2-dimensional collision detection problems are circles and rectangles.

Let's have a quick overview of circle collisions.

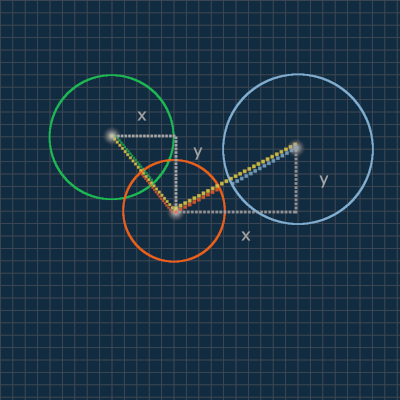

Detect if two circles are colliding

The basic idea is to look at each pair of circles.

- Each circle has a radius.

- If the sum of their radii is less than the distance between the circles, then they are colliding.

How do we find the distance between two circles?

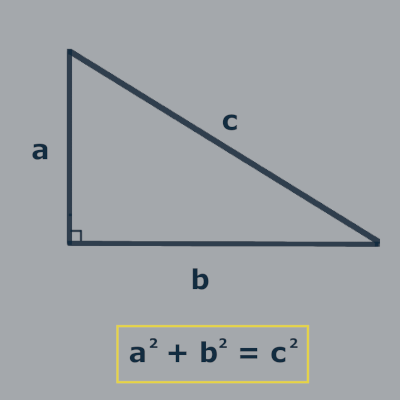

First draw a line between their center x-coordinates, and then a line between their center y-coordinates.

This creates a right triangle where the hypotenuse will be the distance between the two circles.

A refresher of the pythagorean theorem...

If the hypotenuse is smaller than the sum of each circle's radius, the circles must be colliding.

Compare the yellow hypotenuse for each circle pair with their radii to see how this is true.

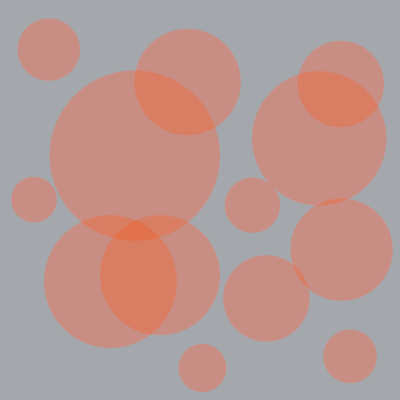

Detect if two rectangles are colliding

- Specifically, we're looking at axis-aligned, or unrotated rectangles in 2 dimensions (x and y) in this post.

- Also known as axis-aligned bounding boxes, or AABBs for short.

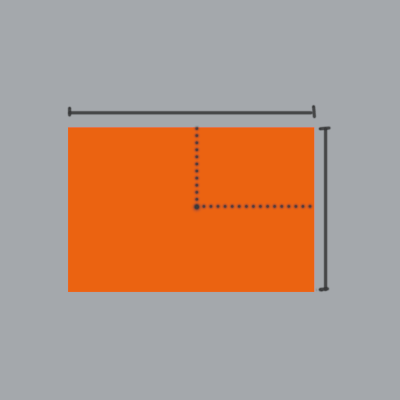

A rectangle is described by an x and y coordinate, along with a width and a height.

We'll use the center point of the rectangle for collision detection purposes.

Instead of a radius, we will use the half-width and half-height of the rectangle, measured from the center point.

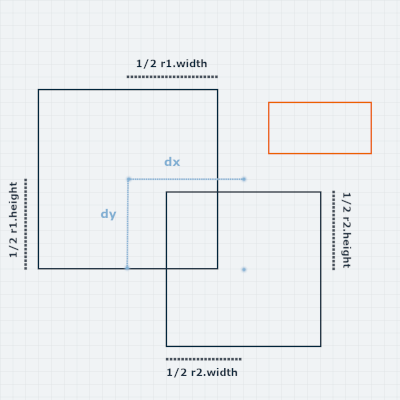

- If the x-distance between two rectangles is less than the sum of their half-widths, there is overlap.

- If the y-distance between two rectangles is less than the sum of their half-heights, there is overlap.

Rectangles are colliding if there is both x and y overlap.

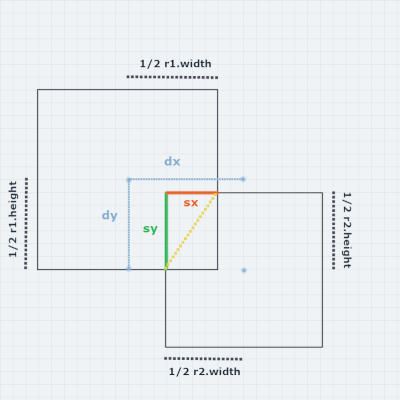

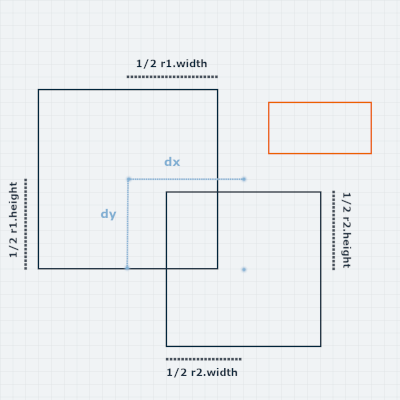

Here we are concerned with two rectangles r1 and r2, which are colliding.

Notice that the red rectangle has y-axis overlap with r1, and x-axis overlap with r2.

But it is not colliding with anyone because if it were it would have both x and y overlap with its collision partner.

Here is pseudocode for detecting the collision between r1 and r2:

r1 = {centerX: 10, centerY: 14, , width: 14, height: 14}

r2 = {centerX: 19, centerY: 21, width: 12, height: 12}

xSize = (r1.width + r2.width)/2

ySize = (r1.height + r2.height)/2

dx = r1.centerX - r2.centerX

dy = r1.centerY - r2.centerY

absX = Math.abs(dx)

absY = Math.abs(dy)

//x overlap

xDiff = absX - xSize

//y overlap

yDiff = absY - ySize

if(xDiff < 0 and yDiff < 0){

//collision has occurred

}

Responding to a collision

Once we've detected a collision, we will respond by adjusting the velocity of the two rectangles to separate them.

To do this, we need to find the direction and speed of the collision, which we will use to adjust the velocities of the rectangles and push them apart.

Velocity

If you remember your physics, velocity is a vector quantity, defined by a magnitude and a direction.

The magnitude of velocity is speed, and velocity represents an object's speed in a certain direction.

Nodes in a force layout have a velocity in both the x and y direction, with attributes vx and vy.

Pushing the rectangles apart

- We're only going to push the rectangles apart along one axis.

- It will be the axis with the least amount of overlap.

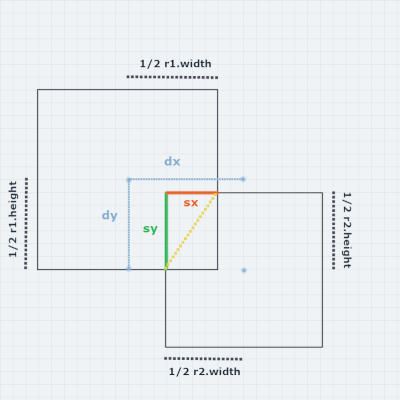

Find the separation vector

The separation vector will tell us a couple of things:

- Which axis has the least amount of overlap, and how much overlap there is.

- The direction of the collision.

We will use this to calculate the collision normal, which is a unit vector that has a magnitude of 1 and gives us the collision direction.

Initialize the vector components.

sx = xSize - absX;

sy = ySize - absY;

In the example collision, you can see that there is less overlap on the x-axis than on the y-axis, so the rectangles will be pushed apart along the x axis until they are separated, which will also resolve the overlap on the y-axis.

The initial separation vector is:

Then do the rest of the calculations.

if(sx < sy){

//x overlap is smaller than y overlap

if(sx > 0){

//only going to worry about x velocity, so set sy to zero

sy = 0;

}

}else{

//y overlap is smaller than x overlap

if(sy > 0){

//only going to worry about y velocity, so set sx to zero

sx = 0;

}

}

if (dx < 0){

//change sign of sx

sx = -sx;

}

if(dy < 0){

//change sign of sy

sy = -sy;

}

- The x overlap is smaller than y, so set sy = 0.

- dx is less than zero, so change the sign sx = -sx

- (dy is also less than zero, but sy is already 0 and would be set to -0)

And the final separation vector is:

Collision normal

To get the collision normal, we divide the separation vector components by the distance, which is the hypotenuse of the triangle created by them - the yellow line in the graphic.

distance = Math.sqrt(sx*sx + sy*sy)

Notice that sy was previously set to zero, since the x-axis has the smallest overlap and we are therefore ignoring the y-axis, so here it breaks down to finding the square root of sx squared, which is just (the absolute value of) sx.

Now to get the collision normal, just divide each component of the separation vector by the distance.

collisionNormalX = sx/distance = -4/4 = -1

collisionNormalY = sy/distance = 0/4 = 0

The collision normal vector is [-1,0].

In general, the collision normal for each direction would be:

- left = [-1,0]

- right = [1,0]

- bottom = [0,-1]

- top = [0,1]

Relative velocity

Next calculate the relative velocity of the rectangles.

- The velocity of r1 relative to r2 is the velocity that r1 would appear to have from the perspective of r2.

- This allows us to treat r2 as stationary.

We will calculate the speed of the collision from the relative velocity and the collision normal.

rVelocityX = r1.vx - r2.vx

rVelocityY = r1.vy -r2.vy

Simply subtract r2's velocity from r1, for each component vx and vy.

Calculate the speed of the collision

The relative velocity and the collision normal are both vectors.

We can take the dot product of these two vectors to get the speed of the collision.

speed = rVelocityX * collisionNormalX + rVelocityY * collisionNormalY

If the speed is positive, that means the rectangles are moving towards each other, so we will need to resolve the collision.

A negative speed means they're moving away from each other and the collision will resolve itself.

We want to take the rectangle mass into consideration, so that rectangles with smaller mass are pushed more than rectangles with larger mass.

Calculate the impulse which is then used to calculate momentum, which is the product of mass and velocity.

impulse = 2*speed / (r1.mass + r2.mass);

Then use this to update the velocity of each rectangle - remember that we're only pushing the rectangles apart along the one axis with the least amount of overlap, so we only need to update one component of the velocity.

In this example it's the x-axis velocity, so we will update the vx attribute for each rectangle.

r2.vx -= (impulse * r1.mass * collisionNormalX)

r1.vx += (impulse * r2.mass * collisionNormalX)

This will push the rectangles away from each other.

If you're interested in learning more about the physics of collisions, this Khan Academy article is a good starting point.

Checking all object pairs for collisions

We've covered detecting and responding to a collision between two objects.

But in a D3 simulation we need to expand this to check for collisions between all object pairs.

One brute-force solution would be to use nested loops to compare all objects to all others, but that would be very slow.

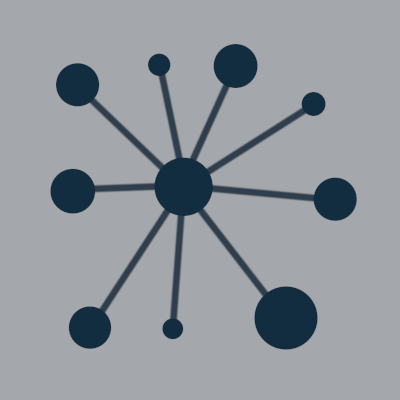

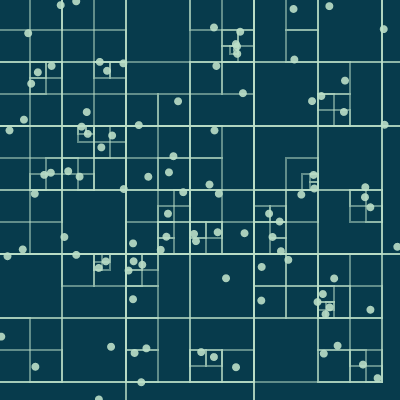

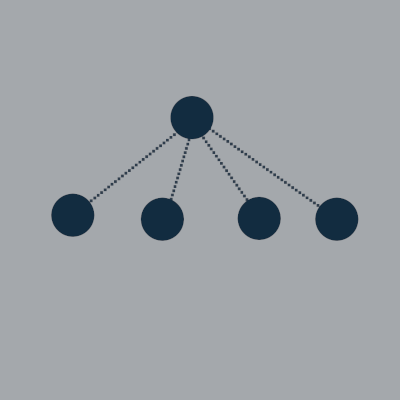

Quadtrees

forceCollide uses quadtrees to search for colliding node pairs in a much more efficient way.

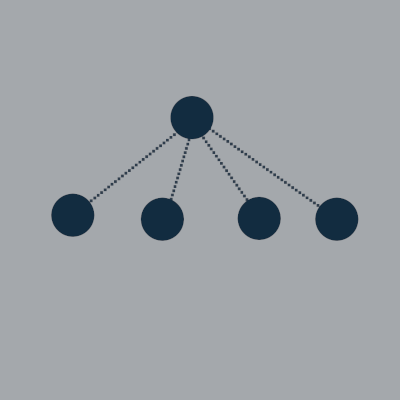

A quadtree is a data structure that is used to partition a 2-D space by dividing it recursively into 4 regions.

If you're familiar with binary trees where each node has two children, in a quadtree each node has up to 4 children.

In a quadtree, each node is either a rectangle or a point, and will have up to 4 children that are rectangles and/or points.

The points are the leaf nodes, meaning they have no children.

We can efficiently determine if two nodes might be colliding by checking to see if they are located in the same quadrant in the quadtree, and continuing to traverse the tree until either:

- They are no longer in the same quadrant.

- Or until we get to the leaves.

So if we are looking at a pair of nodes where one is located in the top left quadrant, and the other is in the bottom right, then we can immediately dismiss them since they are not located near each other to begin with and definitely are not colliding.

If the two nodes are somewhat close, maybe they are both located in the top left quadrant, then we continue to traverse down until they are not in the same rectangle.

Or if we get all the way to the leaf nodes(the points), then we check to see if they are colliding with the calculations from earlier.

Thanks for reading!

My physics is pretty rusty (and to be completely honest, it was not one of my best subjects in school to begin with...) so I used a few sources to work out the calculations in this post.

The main sources I used were:

For more about quadtrees, check out this interactive visualization.

Reach out below or on Twitter @LVNGD with any questions or comments!